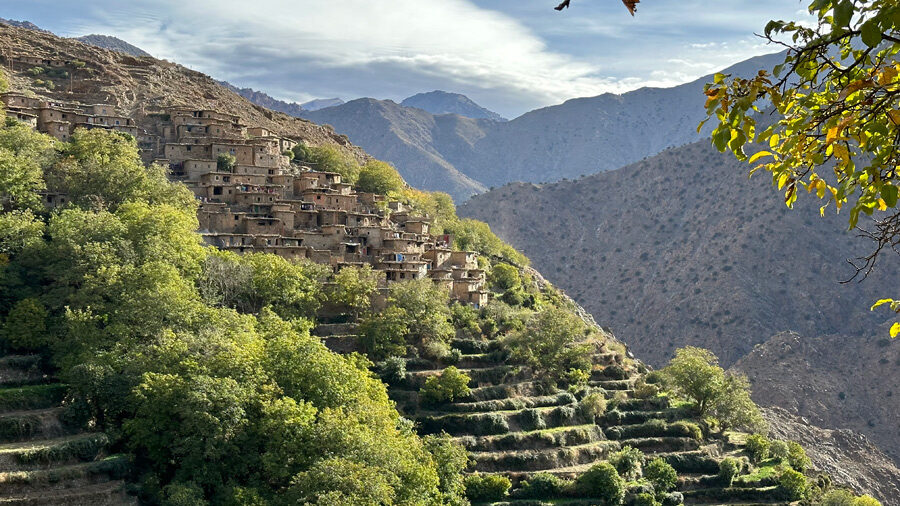

The Upper Zat has carved a magnificent narrow, steep-sided valley out of the granite, with high cliffs on either side. A path runs alongside the river, when it is not crossing it, lined with tall walnut trees that in places form a tunnel of greenery and coolness. Higher up, villages cling to the walls. Still untouched by modernity, they offer breathtaking views of the valley.

The Zat Valley, along with the Ourika and Nfis valleys, is one of three located near Marrakech. The Wadi Zat is the one that flows furthest east. Like the other two, it feeds into the Wadi Tensift, which collects all the water that flows down from the mountain wadis and carries it to the Atlantic.

The wadi Zat flows for 89 km, and its catchment area covers 921 km2, mainly mountains that provide it with water all year round. Its average flow varies between two and five cubic metres per second, but its bed is usually dry when it leaves imin-n’Zat, the mouth of the Zat, a long 8 km corridor before Aït Ourir. The large dam currently under construction at the beginning of this corridor will permanently stop the flow of its waters downstream.

The Zat valley is still a peaceful and remote place, relatively unfrequented. Beyond Tighdwin, halfway along its course, the road penetrates another twenty kilometres into the mountains, heading due south. Towards the end of the road, at the hamlet of Imerguen (1,530 m), the Zat makes a sharp bend, almost at a right angle, towards the south-west.

The Zat makes a bend at the hamlet of Imerguen, and six villages have been built on the steep slopes of the mountain that it has carved out. You can see the new track that partly serves them and, in the background, Assaka Nbaha.

Twenty kilometres further upstream, the Zat rises, bursting vigorously from the rock at the bottom of the valley, barely 500 m higher than at the bend. Along its entire course, the Zat has carved out hard rock, mostly granite, to form impressive cliffs on which a few remote villages cling: Assaka Nbaha, Taliwine, Tinigoon, Timjit, Zarawoon and Taghzit, the last one still some distance from the source.

The river has carved its course through a granite mountain, creating impressive walls above which villages have been built, necessarily perched high up. The village of Taliwine can be seen in the background.

While the water flows at the bottom of the ravine, they have settled at the edge of springs that descend from the heights, from which they have patiently built narrow terraces, some very high up, on the edge of the cliff. Small hamlets have gradually developed around these terraces, where the Aït Zat people lived in relative self-sufficiency until the tarmac road leading to Imerguen, followed by a winding track serving the first villages from above, opened up this isolated world to modernity.

However, cement has only recently made its appearance and the six villages that dot the upper Zat have still retained a relative purity with houses made of earth and stone, depending on the location, which makes passing through them a moment of beauty.

However, to reach their villages, the villagers have kept the habit of following the wadi, which is lined by a long mule track. But when the rains or snowmelt swell the wadi, certain passages downstream towards Imerguen require walking in the water, like mules.

The path that follows the wadi is lined with walnut trees, making for a very pleasant walk.

Encounters are rare on this path, yet it is used by villagers to reach Imerguen, the tarmac road, and break their isolation.

Zaraoune est le seul village en rive droite du Haut Zat, le relief sur lequel il s’est établi semble moins abrupt que sur l’autre rive.

Zaraoon is the only village on the right bank of the Upper Zat, and the terrain on which it is built seems less steep than on the other bank.

Although the villagers have forgotten how many centuries separate them from the first inhabitants, the old walnut trees bear witness to their presence. Those in Taghzit can claim to be several centuries old on the oldest plots, and a few specimens near the springs could certainly be five centuries old.

Behind Taghzit (1,980 m), the last hilltop village, a sloping corridor from the Zat wadi climbs steeply to a first pass (2,823 m) towards the Ourika Valley via Tourcht, just below Meltsen, the lord of the area at 3,560 metres. Continuing further along the Oued Zat, we find the Tizi-n-tilst trail, which also provides access to the Ourika Valley via Azib Agoons.

Taghzit is a village with barely 100 households, spread across two sites on either side of the spring and its stream.

The village is built of stone, a necessity given its isolation, although cement brought up by mule has begun to make an appearance. The stones are grey and hard, quarried from the mighty granite mountain.

The second, smaller part of the village is located further east, on the other side of the spring and its veritable forest of walnut trees.

Agriculture is still thriving here and the terraces are well maintained. As soon as the cold weather recedes, squash, corn, cereals and irises are grown here. The rhizomes of the irises are peeled, washed and sold for use in perfumery.

Several powerful springs flow down from the mountain, which led to the establishment of the village. A large walnut grove has been planted and maintained here, where young specimens stand alongside venerable trees several hundred years old, with diameters of between three and four metres.

From the heights of Taghzit, you can see the course of the wadi Zat to its sources, and the superb rocky ridge of Taska-n’Zat, with its many peaks, the highest of which is almost 4,000 metres, at 3,912 metres.

Access : the starting point of the trail that leads to the Afra plateau from above is located 87 km from Dar Rana, 100 km from Marrakech, on the N9 national road leading to Warzazat.